It was my last year in Arizona. I had begun to slowly get introduced to the idea of being religious at my college Chabad house. I had always been spiritual on the inside, but I never felt like anyone really shared the way I looked at things. But now I had found someones, and they were opening me up to even more ideas.

I was sitting at a pizza place with a friend I had made in the Chabad. He was around the same stage as me, and we were talking about some of the ideas we had been introduced to. We didn’t know it at the time, but we were in love with Chassidus.

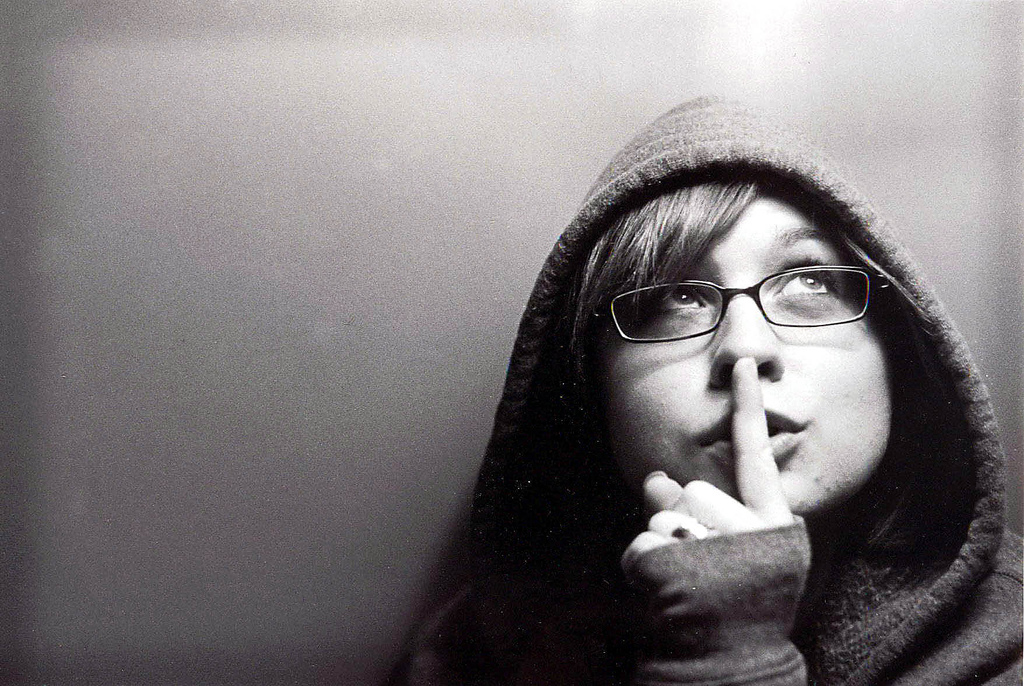

But here’s the weird thing: as the conversation progressed, I remember myself getting more and more uncomfortable. At first, I wasn’t sure why. But the more we talked, and the more we circled around a certain concept, the more my eyes started to dart around the room, wondering if anyone heard us. It was pretty empty in the place, and I couldn’t help but worry about the guy at the register. Did he think we were weirdos?

And so, I slowly changed the subject, tried to talk about the Sun’s playoff hopes. I wasn’t sure, but it seemed like my friend was also relieved.

Since I was young, I’ve been aware of this cultural phenomenon wherein people get extremely awkward and uncomfortable discussing spirituality, and especially the “G-d” word in public. I’m not sure if it’s like this everywhere, or just in the more liberal places I grew up in, but it just seems to be something people are truly afraid to bring up even if they want to.

Maybe it’s because we associate people that talk about G-d and spirituality with crazy evangelicals or crazy hippy mystics. Crazy people, either way. Westboro Baptist Church. Al Qaeda. The crazy preachers on college campuses. People promising eternal reward or eternal damnation.

And so most of us growing up in the secular world felt like talking about this stuff, even if it was a legitimate topic of discussion, even if we wouldn’t have been crazy to discuss it, strayed far away from any such discussions. Even if, like me, it was something we thought about almost obsessively outside of public forums.

Unless we’re crazy, and even if we’re spiritual, most of us consider G-d a four letter word. Something to be avoided at all costs, lest we be associated, even accidentally, with the crazies and the terrorists and the preachers.

Now, to be honest, this seems fair enough. Logical even.

And so, when I started my journey into becoming a religious Jew, I figured that things were finally going to change. I was going to finally be around people that weren’t afraid to say the word G-d or to talk about spirituality in public. And, who knows, maybe I would even become one of those people.

At first, my prediction seemed to come true. Going to a baal teshuva yeshiva (a Jewish school for those becoming religious later in life), there were plenty of people like me. People that were like explorers out in a desert who had just found a reservoir of water. Like me, they had been dying to speak to openly about G-d and spirituality. Like me, they were grateful to finally be in a place that didn’t judge them for that desire.

And so, as time wore on in yeshiva, and I got married, and then returned to yeshiva for another year, I was pretty sure I had finally entered a world where people were comfortable with the word G-d, comfortable with being spiritual in public, comfortable with all that good stuff.

Something has happened recently, though. I’ve been out of yeshiva for a number of years now, I’ve gone out and struck it out on my own, my wife and I have had a child and have started hanging with other married folks with kids. We’ve moved into a religious community. And I guess you could say I’ve also entered the online discussion surrounding religion and Judaism.

And I’ve discovered something.

Religious folks also don’t want to talk about G-d.

Now, that’s a massive generalization, so don’t get me wrong: there are plenty of people that will always feel comfortable talking about spirituality publicly within religious communities. There are events, farbrengens (chassidic gatherings), Shabbat meals, where the whole goal is to talk about spirituality and G-d. There is no question that talking about this stuff is more expected and encouraged.

But what’s been surprising to me, I suppose, is that, much more than I expected, I’ve noticed that same awkwardness when speaking about G-d or spirituality in public. At times, it can feel just as strong as my experience in the pizza shop.

It can even happen at the very gatherings that are meant to encourage discussion about these topics. I’ve been at Shabbat meals, farbrengens, and more, where the word G-d is hardly uttered outside of blessings before eating.

The place I’ve seen this happen the most, though, is online. In publications, blogs, Facebook discussions, Twitter… just about everywhere.

There are a ton of discussions about halacha (Jewish law), religious Jewish culture, scandals, controversies, recipes, etc etc… It’s fascinating, really. It seems that unless we write for something that explicitly covers G-d or spirituality, most of us have trouble discussing those topics.

And the most surprising of all of this: I’m one of those people. I’m back in the pizza shop. Whether it’s my Shabbat table or my blog, even if I do talk about these things, it’s almost reluctant, and in the meantime I’m trying to do everything I can to avoid these topics.

I imagine the reasons are probably not exactly the same as secular culture. Maybe we’re worried that we’re not rabbis, and so aren’t qualified to talk about these topics.

But I think there’s more in common between the two than we think. I think this might not just be a cultural phenomenon, but a human one.

Because the truth is, even those folks that most of us consider to be the crazy G-d talkers, like Al Qaeda and campus preachers, and whatnot… they’re not really talking about Him. They’re just getting lost in their own political insanity and using that word as a vehicle for power.

I think that even people that talk about halacha, get caught up in, argue it, are sometimes avoiding G-d. Not always, but often. I see these discussions going on and on sometimes, especially online. And it seems like the goal isn’t to find out what G-d wants, but to justify what we do.

In other words, I think that even when some of us are talking about G-d, we’re not talking about G-d. Perhaps we’re even avoiding Him.

The truth is, I think most of us, whether we’re religious or not, are afraid to really talk about spirituality. To talk about G-d.

And to be honest with you, I’m not really sure why. If I had to guess, I would think it’s because to talk about G-d and spirituality really means to look inward. You can’t really talk about these things properly without realizing your own faults and inadequacies.

And maybe it’s also because this stuff reminds us how small we are. Reminds us that our daily struggles, the things we want to complain about, the people we want to criticize… all these things aren’t really as big as we think they are. That our accomplishments are really part of something larger.

Or maybe it’s because we don’t want to seem corny. Or maybe because we’re afraid people will think we’re weird. Or maybe it’s because we’ll realize we’re weird.

Maybe it’s all of that. Maybe it’s none of that.

But one thing is for sure: it’s real. It’s something most of us religious folk deal with, and it’s something humanity deals with, whether it realizes it or not.

I suppose that maybe it doesn’t matter why. Maybe what matters is that we realize it. And use it to remind us to dig harder.

Maybe.

Leave a Reply