I’m sitting history class. It’s my freshman year, and the class is called “World History.” We’re on Rome.

Our teacher is telling us about the “Pax Romana” (Roman Peace) and how there was an unprecedented period of peace (more than 200 years) in the region due to Rome’s incredible power and huge territory.

She’s talking about how incredible this was, how rare. How it was actually rare throughout history to ever have long periods of peace that weren’t marked by major wars. War, for much of history, seemed to have been the norm, and peace the exception.

“Which brings us to an interesting question, something that thanks to learning history we can all ask ourselves: are we living through a Pax Americana?”

We had a small debate, but it seemed like almost all of us high school freshman thought we were.

It was the 90s, Bill Clinton was president, the economy was booming, and America’s last war, the Gulf War, was like using chess pieces against someone playing checkers. America was the safest place on earth, and it seemed like everyone was following our lead.

Plus we were in high school. In an upper-middle-class suburb. A bunch of secular Jewish kids who had learned that the world had firmly learned the lessons of “Never Again” and that our lives were the proof of that.

I still remember quite distinctly walking out of that class. I left, and to get to my next class I decided to go the shorter route through the courtyard in the middle of the school. As I walked outside, I looked the sky. The sun was shining. I felt a warmth hit my body. And peace entered my heart.

I wondered to myself how many kids my age had been able to enjoy what I was enjoying at that moment. How many of them felt total comfort and separation from danger. And I realized that I wasn’t just blessed to be living in America, in this place, but also in this time. If time was a planet, I was living on one of the few plots of land that wasn’t raging with war, disease, famine, and/or oppression. As a Jew, I was even luckier.

And I thought to myself, “How blessed I am to be living today. How blessed is everyone in this age and further on. We are safe. Finally.”

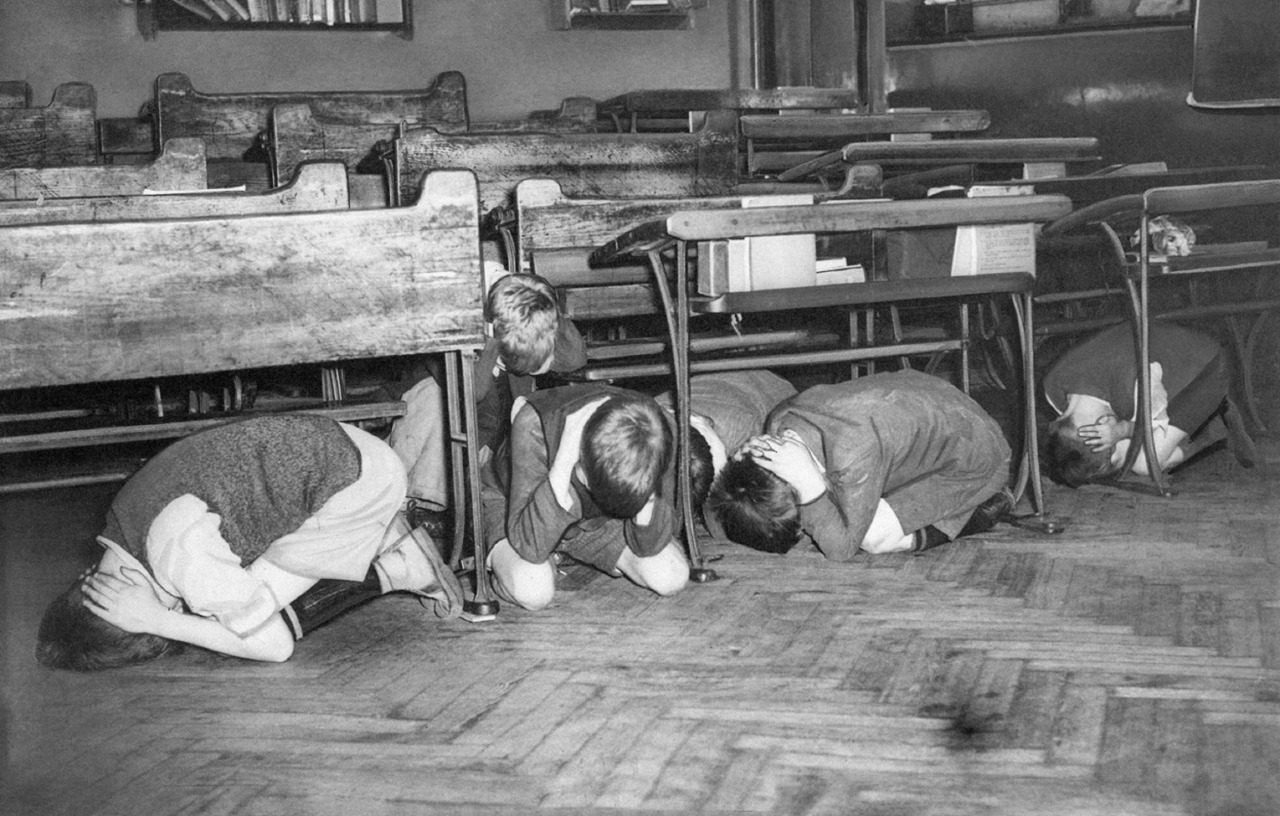

I’m in class, sitting in stunned silence. We all are. I’m a senior. We all are.

It’s not the ‘90s anymore. It’s September 11th, 2001.

We had just finally been released from the classes we all happened to be sitting in when it happened, the classrooms we had stayed in for almost the whole day, all of us watching the televisions in the rooms as smoke plumed out of one building. Then we saw that other plane hit. Then we, us kids, us children between the ages of 13 and 18, had watched as people jumped out of the buildings instead of getting burned alive. Us secular, upper-middle-class, Jewish kids had watched as a man said on television, “I’m sorry, I’m sorry we have to interrupt you,” and the screen shifted to one of the buildings collapsing. In front of our eyes, thousands of people died. Then the other collapsed. Thousands more.

Now, we were in class, as if it made any sense to be in school now, as if any of this made any sense, as if we could think, as if we could act.

Our teacher had had rumors swirling around him since the moment he had been working there. As far as everyone understood, he worked in naval intelligence, and he was so essential that even though he worked as a teacher, they would call him in during emergencies.

“I heard they pulled him out of school once, and a few days later, the Gulf War started,” one of my friends had said.

It turned out that this particular rumor was true.

“Class, I’m going to have to leave for a little while. But I’m here now, so let’s talk.”

He turned the class into a question and answer session, allowing us to ask him anything we wanted. He spoke with us all as if we were adults, as if he was just giving his expertise to us as well he could.

We looked to him to help us make sense of it. He was thoughtful, he was calm, he was focused. He gave us a sense of order, this was the world he had inhabited for his whole life, and to him, this was no aberration. As we spoke to him, it became clear to us that there was never a Pax Americana.

For some reason, I distinctly remember someone asking him about the rocket defense system that was such a debate at the time. They said, “Doesn’t this prove that makes no sense?”

Maybe it sticks out to me because it seemed weird to be talking about liberal talking points at a time like that. Maybe it was because of my teacher’s response.

“Well, these things are complicated. There’s no one threat from one place,” he said.

These things are complicated. There’s not just one threat. And not from one place, either.

Deep down inside, underneath the shock of the day, something shifted. It started to hit me that maybe the world wasn’t constructed in as neatly a way as I had previously imagined. That the answers everyone in this particular town had might not all be accurate.

And that my world wasn’t safe anymore. Maybe it never was.

It’s group therapy time.

I’ve been in the mental hospital for a few days now. Life is finally starting to feel stable, like it makes sense, again. I’ve made friends, and I’m excited to be sitting down with all of them now. Not high from mania like when I first came, not scared like before they took me in because I thought they were working with the FBI. Just excited to have my mind back again.

It’s 2006, 5 years after 9/11. I had spent two months manically trying to figure out when the next terrorist attack would be, my mind convincing me that because I was Jesus I could use math to figure it out. It was the mentally ill way of trying to make sense of something that would never make sense.

But now. Now I feel safe and happy.

A woman is talking, one of my friends. She told me I was an adult at the exact same moment that I was thinking I wasn’t one, and so to me she is a walking miracle.

She’s this tall, sort of strong looking blonde woman, looks like she’s in her forties but that her tan has gotten to her and is making her crack a bit.

I’m excited to hear her speak, I want to learn from her.

“I was nine years old the first time my dad raped me,” she says.

The air escapes my body like I’m a balloon and someone untied me. I had only been to one group meeting up to that point, and I walked out because a woman spoke about how her son seduced her and now she was confused and lost. I thought I had walked out because I was manic and over-sensitive. Maybe it was just because it was painful, unimaginable to hear.

But this was my friend, she had taken care of me, and so I stayed.

She detailed the rapes, spoke about them, how he continued them through her childhood, and how it affected her to this day. She talked about how she was starting to see how it was connected to her doing drugs, to her being here, to her life being shambles.

I watched as this tall, strong, cracked tan woman broke down in front of me, my miracle worker suddenly a helpless child. Streams of tears flowing down her face like a river, like there was no end to the water in those eyes.

I think the therapist leading it helped her. I think other people said things to help her. It’s hard to remember. What I remember is her talking, how she transformed, this woman. How I wanted to cry and hold her, but how I also wanted to be held by her. How confused I was that this happened to such a sweet, such a good, person.

Something shifted deeper in me, something that had been touched on 9/11 and then covered over. I understood for the first time how lucky I had been most of my life to not be exposed to these things. How I was now seeing a world that was alive all around me. Even my town hadn’t been safe from such things, that there were evil and horrible things happening everywhere, that good people lost and were broken, that fathers like hers were out roaming the world while their daughters cried to a room full of people.

No one was safe, and they never were.

“Do you think a Holocaust could happen in America?”

It’s 2008. I’m on Birthright, a free trip to Israel that is in many ways a rite of passage for Jews all over the world. I’m on the “older” trip, for people 22 to 26. For me, this was a free ticket to go study in Israel for yeshiva. But it turns out that this is one of the best times of my life, one of the deepest.

We’re sitting in a circle, all of us soon-to-be “young Jewish professionals” as the bloodsucking Jewish organizations see us as. Secular, upper-middle-class, for the most part. Just like my school in high school.

But I’m going on a different path. My dreadlocks, the fact that I’ll soon be studying in Israel, that I pray with the rabbi in the morning. That world I came from, it’s not mine anymore.

The person who asked the question is the rabbi who’s been along with us on the way. He’s asking it in response to a discussion about why Israel exists. He wants us to wonder if America is indeed as safe as we think it is.

Everyone shakes their heads, you can just see the utter bafflement on their faces. You can see they’re thinking about how ridiculous of a question it is.

I am the only one who nods, who says that he thinks it could happen.

I say, “What makes you feel safe? Why are you so sure? There have always been civilizations that felt safe… until they weren’t anymore. Like Germany.”

But even as I said it, and I knew it, part of me also didn’t really think it could actually happen. I knew it might, I knew it could, but I understood the look of bafflement that crossed the faces of the other Birthright participants.

Those faces probably looked similar to mine when I thought about how lucky I was to be alive in in the 1990s. And even though we had all lived through 9/11, most of us, all of us, saw it as an aberration, not a sign that the universe was in a state of chaos, that such moments were the norm and not the exception. That stability was the exception. That things don’t always go in the direction we hope they will, that humanity isn’t inherently good, that we always seem to have this tendency to slip back into insanity and fascism.

The hospital taught me it could happen, that it was possible, that the world wasn’t safe, that people weren’t treated as well as I had always believed. The woman crying about her father, breaking down, she had taught me that.

And while I wanted the people around me to listen to what I was saying, to understand that the bad could happen, I was still desperately attached to the looks on their faces. The look I wanted back on my own face. One of a complete inability to comprehend that the world can be bad, and that there are people who want to cause others harm.

And, for a little while, I fooled myself into thinking I had internalized their naivety again.

“I think he has a chance,” I say to my wife as I’m sitting on the couch and reading the news on my iPad.

She looks at me. The same face.

“Trump? Seriously? Elad, it’s not possible. There’s no way.”

It’s March 2016, the primaries, and I’ve been getting more and more alarmed. I’ve been reading about how authoritarian tendencies have been increasing in America, and I’m seeing a racism in America becoming reborn, and I’m looking on in wonder as no one else seems to be concerned. As far as I can tell, there’s no reason not to believe this sick, perverted man could become the most powerful person on earth if people don’t speak up right away.

“I don’t think it’s that simple,” I say to her tactfully, partly because I don’t want to scare her because I see how alarmed she is by my thinking, partly because I desperately want to believe her.

“Elad,” she tells me, “Even if he does, you need to believe. You need to trust. Hashem [God] would never let that happen.”

Hashem let 9/11 happen, some part of me thinks subconsciously. He let the woman in the hospital, a good woman, a sweet, angelic woman, who had said the exact right thing that would save my life, get raped by her father. He let her spend the rest of her life in and out of mental hospitals, doing drugs and lost in a world of pain.

Hashem is good, I think, but he also lets terrible things happen.

I look at my wife, I want to tell her all this. I want to explain that the world is bad, that we can’t expect the good out of people. That hoping for the best is what leads to good people to do nothing.

But I see that face. Me in the 90s. The Birthright Jews in 2008. The face I wish had. And I don’t want to rip it up, I don’t want to mess with it. All I’ve ever wanted my whole life is to have that look back on my face.

I try my best to make it again, even though it feels like a mask more than a face.

I say, “I hope you’re right.”

And I mean it.

The results are coming in. The states we all expect to fall, fall. There are no big surprises at first because there are a bunch of obvious ones getting called at the beginning.

A strange sense of calm has come over me for the past week. Despite the anxiety that overcame me for months over believing Trump had a chance, as we closed in on the last week of the campaign, and all the polls showed Trump losing, I finally relaxed. The tapes of him bragging about sexual assault, surely that had done him in.

That week I was the happiest I had been since Trump became a serious contender to lead our country.

I imagine that that night, as the results seemed predictable, I had the face I had in the ‘90s. The face that said, “Ultimately, good will win. Ultimately, people make the right choice.”

Then the Florida results started coming in. If Hillary won this state, it would all be over.

But it wasn’t clear. A decision that was supposed to be made in half an hour after the votes started coming in started to drag out. An hour. Two hours.

Meanwhile, states like North Carolina seemed just as murky.

My stomach, this whole time, fell deep into my gut. The anxiety was back. I knew what was coming, even though I didn’t want to face it. My face was gone.

My friend Matthue messaged me while this was going on. He said: “How are you doing?”

I said: “He’s going to win.”

He replied: “It’s not over yet.”

“I think it might be,” I write. And I know, in some part of me, that it’s true.

Although I’ve tried to quit anxiety medication, the results are so overwhelming that I have to take them. The country that I had felt so safe in in the 90s, that had been the shining light to the world in my young mind, the mind I had tried to tap back into this week, was turning into like every foolish regime of the past. I was watching states fall like flies, collapsing under the weight of fear overcoming concern for others, for Democracy, for the future. Just like every sick revolution of the past.

Before it was officially called, but when it was obvious, I got up and went to my bedroom. My wife, who had gone to sleep unable to handle the tension, woke to the sound of me coming in.

“What happened?” she asked as if she knew.

“Trump won,” I said.

In the dark of the room, the light from the hallway showing her face in the shadows, I saw the transformation that happened to me so many times. The one that I thought it was a merit to fight. But which, seeing it on someone else, made me realize the truth was just the opposite.

Her face, the one that had been so sure for so long that Trump would lose, the one that had argued with me to trust that Hashem would never let something so horrible come to pass, the one that had told me to trust, turned into the one I had in the hospital.

A sudden, quick change into understanding that the world is not predictable. People can’t be trusted to do the right thing. And trust in God does not mean blinding ourselves to the evil inclination in man.

That Shabbat, we sat at our table. We looked in each other’s eyes. We had the same face, we knew it.

We said to each other (it doesn’t really matter who specifically said it as we were saying the same things), “We trust God. But we can’t trust man. We can only trust the strength we’ve been giving, the power to change things ourselves, the voice we have.”

We discussed what we wanted to do, how we’d do it, who we’d reach out to. We decided we wouldn’t give up, we’d fight for what we believed in.

And we understood, finally, that it was not a sign of strength to believe the world will always be good to us. The world is bad to many people all the time. The sweet, beautiful woman was raped by her father. Buildings fall down, brought to dust by the hate of a small group of men. Governments turn against their people, and their people welcome it with open arms.

In other words, to believe the world will always treat us well is selfishness brought about by a life of comfortability. Because the world is never good to everyone, and is, for most people, a very hard, very painful place.

The only reason anything good was ever created, any safety was ever put on the faces of our children, is because there were men and women before us that understood they had to sacrifice to build a better world. They had to fight for the glimmers of good around them.

And so, now, my wife and I, sitting at our Shabbos table, looking into each other’s eyes, we are not scared anymore, or anxious. We are strong. We love each other and we trust each other. We feel more solid than we’ve ever felt.

Because we know that from now on, we will be devoted to being one of those people.

Comments

50 responses to “The World Was Never Safe”

I think growing up in the West in the 90s it was easy to fall into that trap. The Cold War was over, democracy seemed to be spreading across the globe, politics in the West was converging on the moderate, consensual centre, long-running conflicts in places like Israel and Northern Ireland seemed to be ending…

And then over the last fifteen years it’s all emerged as illusion. Russia is still undemocratic and a new Cold War seems to be starting. Politics in the West is increasingly polarized again. The Israeli-Palestinian peace process collapsed. The Middle East is in turmoil. And so on.

But there probably never was a Golden Age, even in the 90s. In the 90s there was genocide in Bosnia and Rwanda and terrorism in Israel, even under the Pax Americana.

Still, the Northern Irish peace has mostly held. I guess some things can get better.

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 39385 additional Info on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 39997 more Information to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 94300 more Information to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 280 more Information to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More on to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 78344 additional Info on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Info here to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 48567 additional Info to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 49780 additional Information to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 12304 additional Info on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More Information here to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 42271 additional Information to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 78446 additional Information on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 8211 additional Information on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you can find 66123 more Info to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Information here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Info to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you will find 84261 additional Information on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Read More here to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More Info here to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Information to that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Find More here on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] Here you will find 1653 additional Info on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]

… [Trackback]

[…] There you can find 32388 additional Information on that Topic: popchassid.com/world-never-safe/ […]